|

Qx v0.7.0.3

Qt Extensions Library

|

|

Qx v0.7.0.3

Qt Extensions Library

|

Bindable properties are properties that enable the establishment of relationships between various properties in a declarative manner. Properties with bindings, which are essentially just C++ functions, are updated automatically whenever one or more other properties that they depend on are changed. These dependencies are established automatically when a property is read during the binding evaluation of another.

The following is a prime example of their use:

The Qx Bindable Properties System can thought of as an alternate implementation of Qt Bindable Properties, and as such its interface is closely modeled after the latter.

The foundation of the system is Qx::AbstractBindableProperty, which represents the general bindable properties interface, while Qx::Property is the primary implementation of said interface. Additional utilities related to the system are accessible through the qx-property.h header.

Qx properties can, for the most part, be used interchangeably with Qt in the context of C++ code (QML integration is not supported, and may or may not be attempted at a later time), just with some behavioral and feature set quality of life changes; thus, for brevity this documentation focuses on the differences between the two systems and if you are totally unfamiliar with bindable properties it is recommended to read the documentation for Qt Bindable Properties first.

The biggest difference between the two is that Qx Bindable Properties were designed with the motivation that bindings are only ever evaluated when absolutely necessary, as there are various situations with Qt properties where extra binding evaluations occur.

Pretty much everything between Qx properties and Qt properties are the same, other than what is mentioned under the Advantages and Disadvantages sections below. Regardless, the following is a non-exhaustive list of some key aspects that both systems share that are important to keep in mind:

This is the largest advantage, and the main motivation for the creation of this system.

As impressive as the Qt Bindable Property system is, there is one aspect of it's behavior that can be frustrating and potentially problematic: It often re-evaluates bindings more times that would appear necessary, presumably due to technical limitations.

Let's take this simple example:

Going off just the notifier callback output, nothing initially looks amiss.

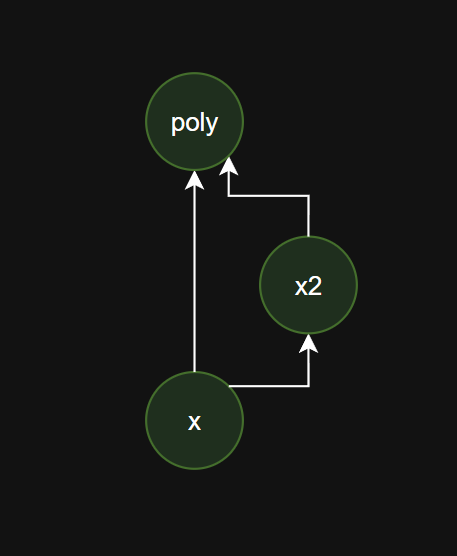

Here we have a dependency graph that looks like this:

Just at a glance we can see that when x is changed, x2 should be updated before poly since the latter depends on both x and x2; however, if we change the example a little to gain some insight into how updates are handled, we see Qt Properties do not do this:

As shown, when we start updating x, the poly binding is evaluated first with a stale value of x2, then x2 is updated, and finally poly is evaluated again. It's possible that declaration order, or some other details may influence this, but that is largely irrelevant, since ideally evaluation count should be consistent regardless of those factors. The takeaway is that the Qt Bindable Properties system does not maximally prioritize minimizing binding evaluations and instead only ensures that the final state of all properties is correct once its update process is finished, while keeping binding evaluations somewhat minimal.

If we then simply change the use of QProperty in the above example to Qx::Property, the output becomes:

which shows that each involved binding is evaluated in a order that prevents any re-evaluations from being required.

At first, although obviously wasteful, it may not seem like a huge deal; however, consider the case where one of these properties might be checked to see if a particular resource is valid (like a pointer) and the other property wraps the resource itself. If the binding that uses both of these properties was evaluated with a stale value for the "resource is valid" property, it might then try to access an invalid resource and cause your program to crash.

Another benefit of Qx's approach is that it handles "incomplete dependency" information in bindings cleanly and has looser restrictions compared to Qt's in the sense that not all code paths need to read from all property dependency on every invocation. For example, if you originally had values you wanted to convert to properties that looked like this:

for the best experience with QProperty you're supposed to do:

so that both round and maybeBouncy are always read within the binding and ball's dependency on both is well-established.

With Qx::Property, you can simply do:

When round is updated for the first time, it will appear like ball only depends on round since maybeBouncy wasn't read due to short-circuiting on the initial binding invocation during ball's construction; however, Qx will handle this gracefully by temporarily "pausing" the evaluation of ball's binding when it sees the dependency on maybeBouncy for the first time in order to ensure that property is updated first. Therefore, ball will not see a stale value for maybeBouncy and ball's binding still only needs to run one time even though it's dependencies suddenly changed!

Qx's implementation is designed so that bindings should never be evaluated more than absolutely necessary. If you've found a scenario in which this isn't true, please open an issue about it on GitHub.

[[nodiscard]] for callback handles to catch subtle bugs in which a callback would be immediately unregistered due to the handle being discardedQPropertyChangeHandler<Functor>Given enough motivation, these drawbacks may be reduced or outright eliminated in the future.